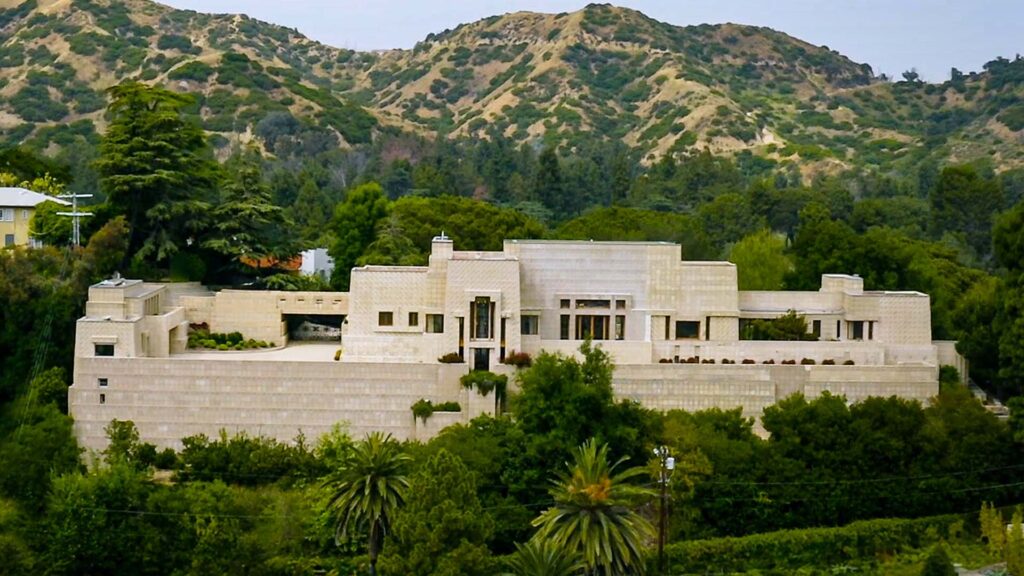

There are more than a few of us who’d enjoy the opportunity to live in a house that appears in Blade Runner; there are rather few of us who would value that opportunity at $23 million, the asking price given in the 2019 Architectural Digest video on Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1924 Ennis House above. Yet even beyond the Wright pedigree and the Blade Runner prestige, the house has also appeared in a host of other films, a screen résumé that begins nine years after its construction, when it made its screen debut as the mansion of a lady auto tycoon in Michael Curtiz’s Female.

In the decades that followed, it went on to provide settings for pictures — usually genre pictures — like The House on Haunted Hill, The Day of the Locust, The Replacement Killers, and Rush Hour. “The Ennis house apparently transcends space and time,” says the narration of Thom Andersen’s documentary Los Angeles Plays Itself. ” It could be fictionally located in Washington or Osaka. It could play an ancient villa, a nineteenth-century haunted house, a contemporary mansion, a twenty-first-century apartment building, or a twenty-sixth-century science lab where Klaus Kinski invents time travel.”

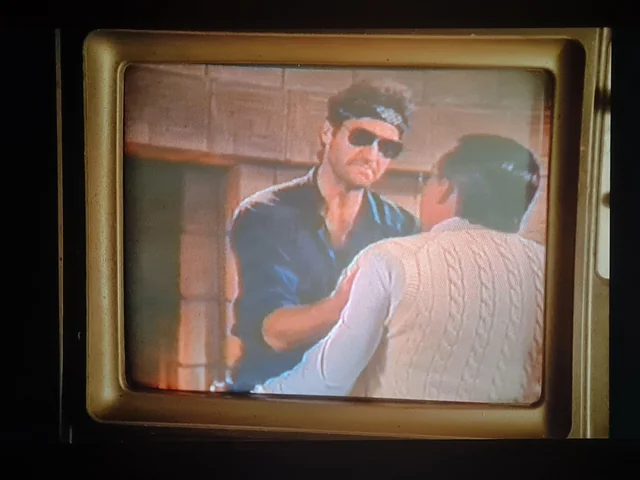

The Ennis House soon became visual shorthand for the home of wealthy, flamboyantly sinister B‑movie villains. That makes all the more notable its use in Blade Runner (a film that made several clichéd Los Angeles locations fresh again), which turns it into the tower where Deckard lives. Even the set-built interior of his apartment uses the same Mayan-motif tiles as the house’s famous concrete-block exterior. But the real rooms of the Ennis House have also received plenty of screen time, not just in the movies but also on television — and even television-within-television, in the case of Twin Peaks’ fictional soap opera Invitation to Love.

As the last of Wright’s Mayan Revival houses, the Ennis House marks the end of his attempt to break into southern California. The architect himself later admitted that it had exceeded reasonable scale: “That’s what you do, you know, after you get going, and get going so far, that you get out of bounds,” he said. “I think the Ennis House was out of bounds for a concrete-block house.” Like much of Wright’s work, it also proved better to photograph than inhabit; despite its most recent and ambitious renovation being completed just a few years earlier, it ended up selling for $5 million below asking price. I appreciate Blade Runner as much as anyone, but $18 million is still more than I’d pay for a 40-minute walk to the subway.

Related content:

That Far Corner: Frank Lloyd Wright in Los Angeles – A Free Online Documentary

A Beautiful Visual Tour of Tirranna, One of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Remarkable, Final Creations

Inside the Beautiful Home Frank Lloyd Wright Designed for His Son (1952)

When Frank Lloyd Wright Designed a Doghouse, His Smallest Architectural Creation (1956)

What Frank Lloyd Wright’s Unusual Windows Tell Us About His Architectural Genius

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.